At MHAScreening.org, we know that among Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) that take a mental health screen, people who identified themselves as multiracial were the most likely to screen positive or at-risk for alcohol/substance use disorders, anxiety, depression, eating disorders, and psychosis.

There’s research that shows that multiracial people have more behavioral health problems than their monoracial counterparts. They face unique stressors, and often find that it is difficult to connect with others – even with other multiracial people. More often than not, the parents of multiracial people will not necessarily understand their struggles. Even among multiracial people, their experiences are so unique, that talking with other multiracial people can feel disjointed, and there can be a failure to connect.

For multiracial people, imposter syndrome goes deeper than our ability to compete with others in skills or knowledge. It can affect our cultural and ethnic identity. When you don’t feel like you “belong” to a group of people, it can make you question your experiences and sense of identity, especially when how identify is often rooted in the way the world sees you.

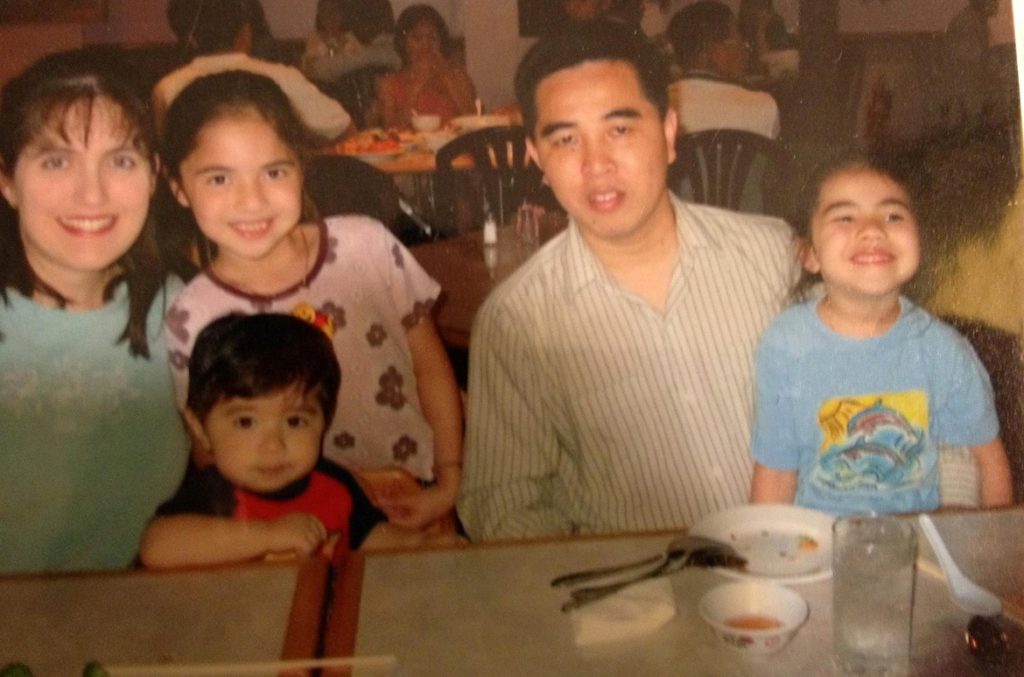

I can only speak to my experience, but being Puerto Rican and Chinese made me feel like I needed to be “more” of those identities in order to be accepted by people who identified as being Chinese or Puerto Rican – including my own family – because I didn’t look like them or I didn’t have the same experiences as monoracial people. I’ve always been considered “half” or “watered down” versions of my Chinese and Puerto Rican identities. Let’s break down some of the issues that multiracial individuals face.

Colorism

Within communities of color, there are examples of how lighter-skinned or people who have more traditionally European features are favored as better or more desirable in these communities. It is important to recognize how even within our communities we uphold ideals of White supremacy based on one’s “proximity to Whiteness.” Multiracial individuals who are darker-skinned – compared to the lighter-skinned “ideal of beauty” held by their communities – can be mocked, shunned, and discriminated against by people within their own community.

Exclusion/isolation

Multiracial individuals can often feel excluded from their communities. You’re “too much” of something or “not enough.” My own extended family was very loving and accepting of my little mixed family, but there was always an internal sense of being different. I didn’t look like them, I couldn’t speak like them, and I didn’t have the same experiences as them. One known systemic example of this type of exclusion of multiracial people is Japan’s obsession with the “Hafu” (“half”) look while simultaneously denying acceptance, rights, and even citizenship to multiracial individuals in Japan.

This is especially egregious when multiracial individuals who match the ideal “Hafu look” like Kiko Mizuhara are heralded for their beauty and accepted as Japanese, while multiracial individuals who aren’t are considered foreigners, regardless of how they identify or if they had lived in Japan their entire lives. However, even with the love that Mizuhara experiences as a celebrity in Japan, she has also struggled with her biracial identity

Lack of Representation

A strange trend that has been happening in media has been the use of multiracial identities to cast White actors or using multiracial individuals to cast characters who are ethnically monoracial. A couple of examples include the casting of:

- Lana Condor who is of Vietnamese descent to play the role of Lara Jean Covey, a character that is canonically Korean and White;

- Henry Golding who is of Malaysian and English descent to play the role of Nick Young, a canonically Chinese-Singaporean character; and

- Emma Stone who is a White American to play the role of Allison Ng, a character that is canonically Asian and Hawaiian.

I’m not saying that only multiracial characters should be played by only multiracial individuals and vice versa, but there’s definitely a deflating feeling when you get excited about seeing a character similar to you, but are disappointed to not see an actor that represents that identity. This is complicated and ongoing discussion among multiracial individuals and there’s no right or wrong answer, but something to think about. Hollywood has never had a great track record in terms of casting appropriately – especially for people of color. Overall, there are not enough BIPOC or multiracial roles to go around in the first place, and I do not blame actors of color for taking what they can get.

Privilege

It is important to recognize for some multiracial individuals, you have a lot of privilege depending on the way people see you. For example, lighter-skinned, White-adjacent, or White passing multiracial people have significantly different experiences than others. In a 2013 Medium article, the author identified as being biracial – half Black and half White – and they and their sibling had significantly different experiences, because the world identified them as White and their sibling as Black.

While this privilege doesn’t negate negative experiences due to identity or other struggles of being multiracial, it’s important to realize the privilege that comes with being able to “come out” as an identity – which is different than for people who are automatically stereotyped based on their appearance. Even if you aren’t accepted by your community – especially if you have Black or Indigenous heritage – it’s still important to show up for issues of injustice anyway, and use the privilege you do hold to navigate spaces that others cannot.

This is a tough pill to swallow. I have been there. But it is something that we need to understand, learn, and grow from